Somehow a quick unedited email or text just doesn’t resonate like the slap of an envelope dropped through the mailbox.

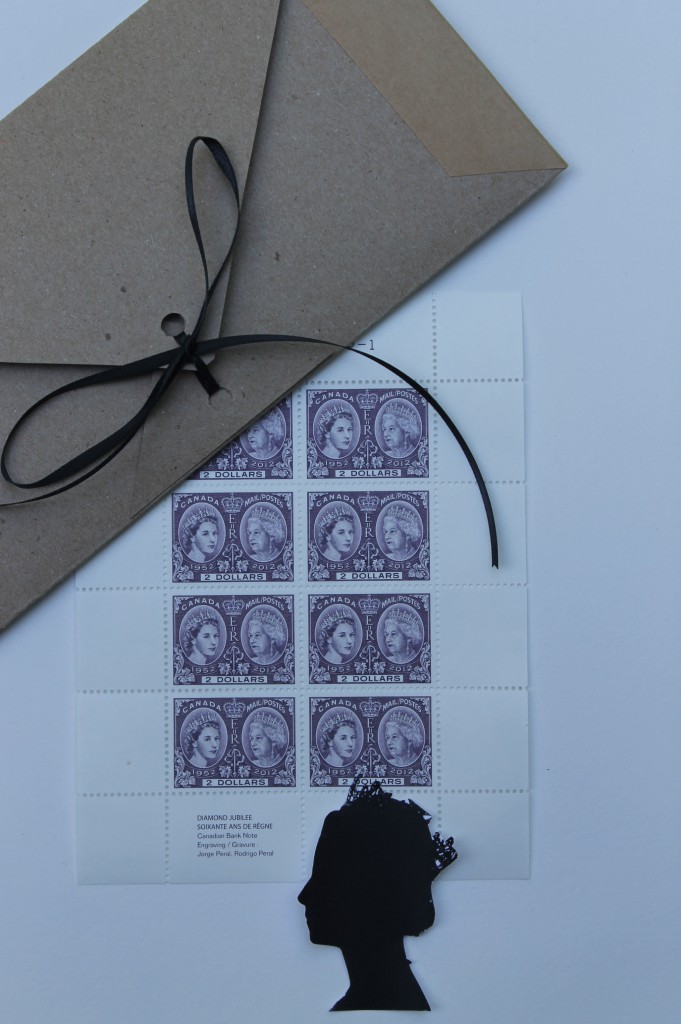

There is no (or very little) ritual to writing via electronic mediums. We don’t gather pen, paper, envelopes and stamps. There is no tactile experience of the handling of the paper, no smell of the ink and no gummy taste from the envelope seal and stamp. We send a brief overview of what we would have said, almost as a duty, a quick afterthought, often in phrases without grammar or punctuation.

Perhaps worse is the fact that by making letter writing obsolete we have no permanent stored record. Nothing, (unless we save all our emails and who does?) to look back on, to inform future generation, to help chart history. Whole biographies have been written around letters; published to give others an insight into an intimacy that the people corresponding shared. Somehow I can’t imagine this same intimacy being gleaned from email’s and text messages. I can’t imagine the biographer asking to access someone’s computer or phone and retrieving shared messages. And, even if this were to happen, how clinical to take some cyberspace rudimentary messages and try to pass them off as full factual accounts.

Finally, how sad for my daughter, and the predominance of a generation who mediate relationships through text messages, that she will never have a love letter. Just an abbreviated list of phrases or words (If she doesn’t delete them), staring at her from a small, hard plastic screen.